Daily Sh5.1 Billion Debt Repayments Strain Kenya's National Budget

Kenya's soaring national debt is creating a fiscal crisis, diverting funds from essential services and raising questions about the nation's financial future.

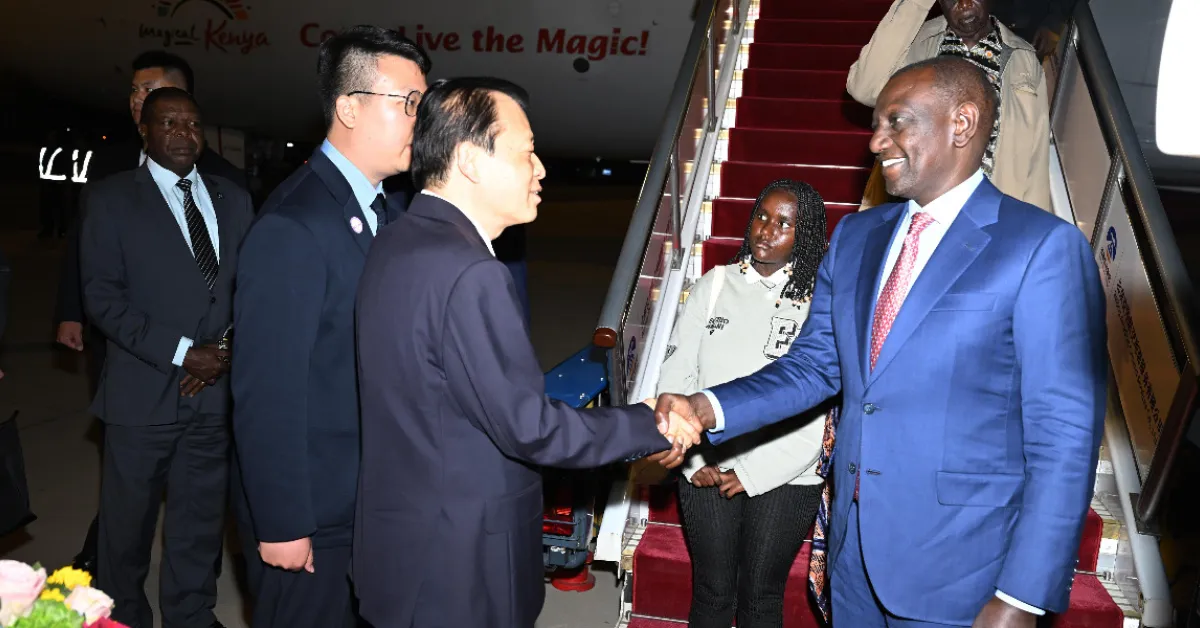

President William Ruto's recent trip to China yielded promises of infrastructure projects and financial support, but the country currently struggles to service its staggering Sh5.1 billion daily debt burden. Kenya's current fiscal year necessitates allocating Sh1.866 trillion to debt servicing, consuming over half the national budget. To contextualise, the Ministry of Health's entire annual expenditure of Sh127 billion could be covered by just two weeks' worth of these daily debt repayments. The total national debt has surged to Sh11.02 trillion.

The roots of Kenya's debt crisis lie in the borrowing patterns of previous administrations. While former President Mwai Kibaki maintained a measured approach, leaving office in 2013 with a national debt of Sh1.894 trillion (51.7% of GDP) and manageable daily debt servicing costs of Sh400 million, his successor, Uhuru Kenyatta, embarked on an era of ambitious borrowing. Under Kenyatta's leadership, the national debt ballooned by Sh6.7 trillion, escalating daily repayments to Sh2.1 billion by 2022.

The Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) project exemplifies this period's borrowing spree. Financed by a $3.23 billion loan from China's Exim Bank in 2014, the SGR was envisioned as a transformative infrastructure project, reducing transport costs and promoting regional integration. However, delays, Uganda's withdrawal from the extension plan in 2018, and annual maintenance expenses of $439 million have rendered the SGR a financial burden.

Critics argue that unchecked optimism led Kenya into a precarious financial position, with the SGR serving as a cautionary tale of ambition overshadowing fiscal prudence. Kenya's debt woes are further compounded by the Eurobond scandals. In 2014, the nation raised $2.75 billion for infrastructure projects, but Auditor-General Edward Ouko's investigation revealed irregularities in the handling of the funds.

The proceeds were deemed fungible and untraceable, sparking public outrage. Subsequent Eurobond transactions deepened concerns, with fears of default forcing Kenya to repurchase billions worth of bonds while simultaneously borrowing anew to finance repayments. Economist Kwame Owino has described this cycle as "robbing Peter to pay Paul." Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi has acknowledged that much of the borrowing between 2014 and 2019 was excessively expensive, exacerbating Kenya's vulnerability.

The debt-to-GDP ratio now stands at 65.6%, significantly above the IMF's recommended 40% threshold for emerging economies. The weakening shilling and rising public dissatisfaction further compound the challenges facing President Ruto's administration. The need to allocate substantial resources to debt repayments leaves limited room for investment in critical sectors such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

Corruption has also contributed to the debt crisis, with high-profile scandals, such as the National Youth Service debacle costing Sh11 billion, siphoning funds that could have alleviated the economic strain. The combination of reckless borrowing and mismanagement has placed Kenya in a debt trap, necessitating further borrowing simply to meet existing obligations.

Add new comment