Madaraka Day: The Moment That Shaped Kenya’s Path to Self-Governance

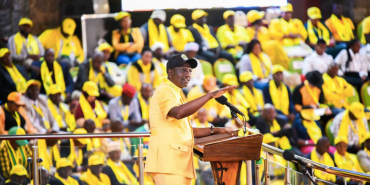

As Kenya commemorates its 63rd Madaraka Day, marking 63 years of self-governance since June 1, 1963, the nation confronts enduring challenges that mirror the formidable obstacles faced by its founding leaders.

While the inauguration of Jomo Kenyatta as Prime Minister symbolised a decisive break from colonial rule and ushered in an era of hope, the dreams of national unity and equitable governance remain works in progress, echoing throughout the country's present-day political landscape. Sixty-three years ago, the symbolic transfer of power occurred at what is now Harambee House, formerly the Ministry of Works. Kenyatta, in traditional attire, and his ally Oginga Odinga, addressed jubilant crowds on Coronation Street, now Harambee Avenue, signifying the end of colonial administration and a nation stepping into self-determination.

However, the celebrations masked deep-seated challenges that continue to resonate today. The primary challenge revolved around forging a cohesive national identity from a diverse tapestry of ethnic groups, each with distinct interests and historical grievances. Successive administrations have grappled with this intricate social fabric, from the single-party dominance of Kenyatta and Daniel Arap Moi to more recent experiments with coalition governments and power-sharing arrangements. The overarching goal has remained the pursuit of national unity, a central theme in Kenyan politics.

Madaraka Day symbolised the culmination of struggle, negotiation, and sacrifice. It was a moment of profound optimism, reflecting a collective belief in Kenya's capacity to chart its own course free from colonial constraints. Kenyatta's declaration of "one of the happiest moments in my life" encapsulated the nation's yearning for self-determination. However, underlying tensions began to surface even amidst the initial euphoria. The camaraderie between Kenyatta and Odinga, prominent on that historic day, was ultimately undermined by ideological differences and external interference.

The British government, wary of perceived communist influence within Kenyatta's administration, actively sought to sow discord between the two leaders, precipitating long-term political repercussions. Odinga's subsequent exclusion from the government ignited anger and disillusionment, perceived by many as a betrayal of independence ideals. His autobiography, "Not Yet Uhuru," chronicles the resulting national discontent. This event exposed the fragility of the ruling coalition and the internal power struggles within the Kenya African National Union (KANU), where concerns existed regarding a strongly centralised party organisation.

The pursuit of personal and regional influence also manifested in the formation of ethnic-based political parties. Paul Ngei's establishment of the African People's Party in 1963, ostensibly to consolidate control over Ukambani politics, established a precedent that continues to plague Kenyan politics. The tendency of political leaders to prioritise ethnic loyalty over national ideology perpetuates a cycle of division and undermines efforts towards genuine national unity. KANU's victory in the pre-Madaraka elections, securing a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, allowed Kenyatta to form the government.

However, this victory also established a "winner-takes-all" political culture, where the opposition was frequently marginalised and suppressed. This dynamic continues to impede the development of a truly inclusive and representative democracy. Despite these challenges, KANU presented a unifying manifesto, pledging to address colonial legacies, foster national unity, and dismantle entrenched inequalities. Kenyatta reassured the white settler community, guaranteeing protection of their rights and property under the new government, and promising a future built on equality, stability, and the rule of law.

However, the persistent spectre of tribalism remained a significant obstacle. The violence following the disputed 2007 elections, fueled by deeply tribalized political affiliations, served as a stark reminder of the fragility of national cohesion. Kenyatta's 1960s question of whether a cohesive nation could emerge from a divisive multi-party democracy remains highly relevant. The concept of "Majimboism," or federalism, advocated by the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) and supported by settler representatives, was perceived by Kenyatta and his allies as an attempt to delay independence and obstruct the establishment of a strong, centralised African government.

KADU envisioned powerful regional governments, particularly in areas under its control, designed to thwart Kenyatta's ascent to national leadership. Post-Madaraka, the regional governments struggled with financial instability and administrative inadequacies. This provided Kenyatta with the justification for centralising power. Tom Mboya, Kenyatta's ally and Minister of Constitutional Affairs, strategically engineered defections from KADU, co-opting opposition members and discrediting them as retrogressive or tribalist. By 1964, Kenya had become a de facto one-party state, a strategy that would be refined by subsequent administrations to suppress dissent and consolidate power.

Furthermore, Kenyatta strategically targeted internal dissent within KANU. Jaramogi Odinga's leftist and populist stance, aligned with socialist movements, was viewed as a threat to Kenyatta's pro-Western, capitalist agenda. Kenyatta used a combination of persuasive and coercive tactics to weaken Odinga's influence and ensure that KANU reflected the interests of the conservative elite. State media branded Odinga and his allies as radicals, silencing domestic dissent and reassuring Western powers of Kenya's alignment during the Cold War.

While Kenya did not formally outlaw opposition parties until 1982, Kenyatta's post-Madaraka strategy effectively established one-party dominance without a constitutional amendment, representing a clever form of legal authoritarianism. This legacy of political manipulation and suppression of dissent continues to cast a long shadow over Kenya's democratic development. Even Mwai Kibaki, who ended KANU's 40-year rule, faced similar headwinds. Under Moi's leadership, KANU had overseen economic stagnation and rampant cronyism, transforming public institutions into vehicles for elite enrichment.

As Kenya marks its 63rd Madaraka Day, the nation remains under construction, grappling with the fundamental challenges that confronted its predecessors. The pursuit of national unity, economic equity, and genuine democracy remains a continuous struggle, demanding vigilance and a renewed commitment to the ideals of self-governance.

Add new comment