Kenya Battles Rising Wildlife Trafficking of Smaller, Endangered Species

Kenya, a nation renowned for its dedication to wildlife preservation, confronts an escalating challenge as the illegal trade in animal and plant products undergoes a significant transformation.

Recent judicial proceedings and law enforcement actions reveal a concerning trend: traffickers are diversifying their targets, focusing on smaller, less conspicuous species, thereby complicating detection efforts for authorities. The recent apprehension of two Belgian nationals, a Vietnamese citizen, and a Kenyan national, accused of attempting to smuggle 5,000 live garden ants, underscores this paradigm shift. The insects were meticulously packaged in modified test tubes, designed to sustain them for extended periods, highlighting the ingenuity and resources employed by these smugglers.

This incident exemplifies the evolving nature of the international black market for wildlife trophies, where traffickers increasingly target species that, while not traditionally associated with smuggling, command significant value in Asian and European markets. Historically, Kenya's struggle against the illegal wildlife trade has primarily focused on the poaching of elephants and rhinoceroses, driven by the exorbitant prices commanded by their tusks and horns. However, the discovery of garden ants, pangolin scales, and dried butterflies among seized contraband indicates a growing demand for smaller, often critically endangered, wildlife.

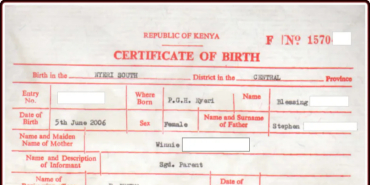

Pangolins, recognised as the world's most trafficked mammals, epitomise this shift. A notable case in 2017 involved the arrest of Bavon Mukoko Lilungu and Wambua Mbithi at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA), found in possession of 100 kilograms of pangolin scales concealed beneath giraffe and elephant carvings. Despite the presence of seemingly genuine customs stamps from the Kenya Revenue Authority, subsequent investigations revealed these stamps to be counterfeit.

Lilungu and Mbithi were each fined Sh1.14 million, with the alternative of a two-and-a-half-year prison sentence. Their case underscored the immense value of pangolin scales on the black market, where a single kilogram could fetch as much as Sh60,000 at the time. A later seizure in 2018 revealed an even more dramatic increase in value, with 2.75 kilograms of scales valued at Sh1.4 million per kilogram. Despite their critical conservation status, public awareness of pangolins remains limited within many Kenyan communities. The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) has identified misinformation and a lack of public knowledge as significant factors contributing to the species' vulnerability.

In some instances, pangolins are killed simply due to their unfamiliarity to local populations. While pangolins have emerged as a significant target for traffickers, other species have also come under increased threat. Ezekiel Karim Kilumile was apprehended for smuggling 201 dried butterflies and guinea fowl skins from Tanzania into Kenya. Crossing the Lunga Lunga border in Kwale County, he initially faced a substantial fine of Sh21 million or a 12-year prison sentence. However, following an appeal, the penalty was reduced to Sh300,000 or three years' imprisonment, which he completed in 2022.

The case raised critical questions about Kenya's role in the wildlife trophy trade, specifically whether the nation serves as a hub for domestic clientele or a transit point for international buyers. Similarly, the arrest of Mwangangi Mutambuki in Machakos County for possessing leopard hides and elephant tusks suggested the involvement of organised criminal networks. Experts from the National Museums of Kenya confirmed that the hides had been preserved, suggesting a highly coordinated operation.

Even plant species have not been spared from this illicit trade. In 2023, the Kiambu High Court overturned a controversial magistrate's ruling that had allowed two individuals to retain five tonnes of aloe vera, a protected species with a black market value of Sh4.5 million. Sea turtles have also faced significant threats, particularly in coastal areas. In 2018, KWS officers, acting on intelligence, arrested two fishermen on Kui Island, suspecting them of poaching a turtle.

A freshly stripped shell, weighing five kilograms and measuring 90 centimetres, was discovered near their shed. Although the magistrate’s court initially convicted the two, citing circumstantial evidence, the High Court overturned the verdict, citing the lack of direct proof and the possibility of other individuals being involved. The economic incentives driving the illegal wildlife trade cannot be overstated. High demand from international markets, particularly in Asia, fuels poaching and trafficking activities.

Pangolin scales, for instance, are highly sought after for their purported medicinal properties and use in traditional rituals. Other wildlife trophies, such as butterfly specimens and leopard hides, cater to collectors and luxury markets, while turtle oil and aloe vera are used in cosmetics and alternative medicine. This diverse range of uses has broadened the scope of trafficking, complicating efforts to combat it effectively.

For many local communities in Kenya, the black market presents a tempting source of income. However, the long-term consequences are dire. The depletion of rare species not only threatens biodiversity but also undermines the country’s tourism industry, a vital pillar of the economy. Kenya’s judicial system has faced scrutiny regarding its handling of wildlife crime cases. While fines and prison sentences have been imposed in many instances, inconsistencies in sentencing and enforcement have sparked debate. The reduction of penalties for some offenders has raised concerns about the deterrent effect of current laws.

Add new comment