Three Years of Ruto: Views from Kenyans Living Abroad

Kenyans living abroad are divided over President William Ruto’s performance midway through his first term, with some welcoming reforms while others criticise unmet promises and persistent governance issues.

One of the key developments under Ruto’s administration has been the creation of the State Department for Diaspora Affairs, the first within the Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs. Professor Kefa Otiso, based at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, sees this as a positive step towards better engagement with overseas citizens.

He also cites the introduction of Mobile Consular Services (MCS), which have brought essential services such as passport renewals, birth registration, and document certification closer to diaspora communities in major cities worldwide. According to Otiso, these services could enhance long-term ties between Kenya and its global citizens if consistently implemented.

However, concerns remain. Otiso has raised issues around ongoing corruption and high youth unemployment, arguing that financial mismanagement continues to obstruct economic progress.

His views are shared by Professor Eric Otenyo of Northern Arizona University, who says a deeper cultural shift is needed within the political leadership. He criticises what he describes as a governing mindset focused on personal gain rather than public service, likening it to a colonial dynamic where power is exercised for the benefit of the few.

The government’s affordable housing programme, one of its flagship initiatives, has also faced scrutiny. Designed to reduce the country’s housing deficit, the programme has been marred by reports of corruption and irregular procurement processes.

Critics say the project has become commercialised, with units resold to the public despite being financed by taxpayers, and priced beyond the reach of many intended beneficiaries. Professor Mukoma Wa Ngugi of Cornell University offers a harsher critique, dismissing the administration’s record as lacking any lasting achievements.

He compares its governance style to organised crime, accusing it of prioritising greed over public interest. For Ngugi, the failures reflect broader structural issues within Kenya’s political and economic systems, rather than the shortcomings of one individual.

Several other campaign pledges have struggled in implementation. The rollout of Competence-Based Education (CBE), though well-intentioned, has suffered from underfunding. Many schools and tertiary institutions report financial strain, and teachers’ unions have held regular protests over unpaid benefits and unmet agreements.

The Hustler Fund, a digital microloan scheme targeting small businesses and informal workers, has also drawn criticism for high default rates and limited impact, raising doubts about its long-term viability. Economic challenges remain significant. While the Kenyan shilling has shown some nominal stability, the cost of essential goods continues to rise, placing pressure on household budgets.

Remittances from the diaspora, particularly from the United States, which contributed approximately $4 billion in the past year, have played a critical role in supporting the economy. In foreign affairs, Kenya has made several notable moves. Its designation as a Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA) by the United States marked a diplomatic milestone, alongside a reduction in attacks linked to Al Shabaab.

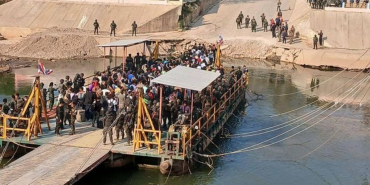

However, proposed amendments to the US National Defence Authorisation Act could threaten this status, prompting the Kenyan government to increase its diplomatic outreach. Kenya’s leadership of the Multinational Security Support Mission in Haiti, launched in 2024, further reflects the Ruto administration’s international ambitions.

While the government has framed the deployment as a moral responsibility, its long-term value for Kenya remains unclear, particularly among diaspora communities observing from abroad.

Add new comment